在南方湿地、海岸与山谷之间,

我追踪身体的力量如何穿过土地:

将步法、队形、击节、传力

编织成一种让世界运转的节奏系统。

从楚地龙灯到潮汕英歌舞,

从旱船到火龙,

身体力是一种让人群对齐、

让节奏生长的文明能力。

Across wetlands, coastlines and mountain valleys,

I trace how the force of the body moves through landscape,

weaving steps, formations, rhythm and shared momentum

into a living system of Rhythm Civilization.

From Chu lantern dances to Chaozhou Engko,

from dryland boats to fire dragons,

Body Force reveals a civilizational skill—

the ability of people to align, move,

and generate rhythm together.

英歌舞为何一眼就让人“有感觉”?从潮汕的步法、阵法、衣甲与节奏出发,解析一种靠身体对齐、靠材料放大、靠街巷生成的集体节律。与楚地湿地步法、巴西战舞 Maculelê 同构的全球节奏逻辑,在正月里于潮汕再度亮起。

Why does Yingge dance feel instantly familiar to the body? This piece examines its steps, formations, armor-like costumes, and stick rhythms—revealing a system where movement aligns, materials amplify, and streets become collective engines of rhythm. Linked to Chu wetland step logic and Brazil’s Maculelê, Yingge shows how civilizations form through synchronized bodies.

这一篇记录黄陂僵狮子如何用身体发动节律。

起乩的“马脚”、贴身的村道、火力的热、走地界的路,

把正月的村庄重新亮一次。

狮子不是被舞起来的,

而是被身体震出来的;

村庄不是被画出来的,

而是被动作重新连起来的。

这是一个靠颤、靠火、靠贴近才能启动的乡土节律系统。

This piece explores how the Jiangshizi (Stiff Lion Dance) of Huangpi

uses the body as an engine of rhythm.

The trembling majiao, the narrow village paths, the heat of firecrackers,

and the boundary-walking ritual together

re-ignite the village each lunar January.

The lion is not performed—it is shaken alive by human bodies.

The village is not drawn on a map—it is reconnected through movement.

This is a rural rhythm system powered by tremor, fire, and touch.

《楚地龙灯》不是在描述一个春节的热闹项目,而是在追踪一种“湿地身体算法”如何被点亮、放大,并以光的方式重新走过乡土。龙灯的动作——方向先行、摆幅恒定、中心推进——并非表演技巧,而是湿地文明古老的走路方式,被几十个身体合成一条脊柱,在黑夜中显形。火不是舞台效果,是显影剂;光不是照明,是路径。龙灯的意义,不在装饰,不在节庆,而在于:一个社区如何通过身体对齐、火光校准与路径确认,完成一年一次的“文明重新上路”。

“Dragon Lanterns of Chu” is not a study of festive spectacle but an inquiry into how a wetland civilization reactivates its oldest movement algorithms through light. The dragon lantern’s motions—direction-leading, amplitude-holding, core-driven—are not performance techniques but embodied memories of how people once moved across unstable ground. Dozens of bodies merge into a single spine; fire becomes a revealing agent; light becomes a pathway. The significance of the dragon lantern lies not in decoration or celebration but in how a community recalibrates itself—by aligning bodies, syncing rhythms, and retracing the essential routes that allow its world to start again each year.

本篇从采莲船、彩船与旱地划龙船等年节船舞切入,

不以器物形制为主,而以“身体作为船”的底层算法为核心。

通过三个动作结构——方向先行、摆幅恒定与中心推进——

解析湿地文明如何在河网退去之后,

仍以步法保存“水的逻辑”。

文章提出:

不同地区的年节船舞并非彼此模仿,

而是同源于一条共同的湿地身体记忆。

在年节中,人以身为舟,

让一条看不见的河再次被走出来。

This essay examines New Year “boat dances” across the wetland cultural belt—

from lotus boats to decorated stage-boats and land-based dragon boats—

focusing not on their shapes but on the shared bodily algorithm that animates them.

Through three structural principles—direction leading before steps,

constant lateral sway, and core-driven propulsion—

the text reveals how wetland civilizations preserve the logic of water

through movement long after the waterways have shifted or vanished.

Rather than regional imitation, these boat dances emerge from a common

embodied memory shaped by river networks.

In the New Year season, the body becomes a boat,

and an unseen river rises again under the dancers’ feet.

《麻城花挑》是一支在湖北大别山坡地上长成的行路舞。

它把劳动步与爱情身绑在同一段节奏里,

让“走路、做事、喜欢一个人”

在同一个动作系统中成立。

花挑的三人结构——妹、嫂、哥——

是一套能在任何场地启动的小型协作算法:

妹定方向,嫂调节位置,哥稳住节拍。

步是地形教的,形是三人维持的,

动作则在村落的日常路径中不断被更新。

随着武合铁路贯通、麻城北站投入使用,

花挑并未因外来速度而改变。

高铁带来的是可抵达性,

让更多人能走进这些动作原本就存在的生活场景。

在麻城,路到了,舞就能被看见。

“Macheng Flower Dance” is a walking-based folk choreography shaped by the slopes of the Dabieshan region.

It binds two seemingly unrelated movement logics—

the steps of labor and the gestures of affection—

turning everyday walking, working, and loving

into a single bodily system.

Its three-person formation—the younger girl, the elder sister, and the brother—

functions as a portable cooperative algorithm.

The girl sets direction,

the sister adjusts spacing,

and the brother stabilizes rhythm.

The steps come from the terrain;

the formations emerge from shared movement;

the dance survives by adapting to whatever space it enters.

With the opening of the Wu–He High-Speed Railway

and the operation of Macheng North Station,

the dance has not changed.

High-speed rail does not alter tradition—

it only increases access,

allowing more people to walk into the landscapes

where these movements have always lived.

In Macheng,

when the road arrives,

the dance becomes visible.

《峡江古声|长江峡江号子》以节奏叙事重访纤夫在急水中协作的方式,记录号子如何在雾气、浪声与断续视线里完成“瞬间对齐”,让几十副身体在同一时间点落力。三峡蓄水后号子退出生活现场,但协作的算法仍留在声腔的骨架里。本篇呈现平水、见滩、冲滩与滩后的四段节奏结构,让一种来自险滩的集体智慧在当代被重新听见。

This article revisits the rhythmic logic of Xiajiang work chants—

a coordination system that enabled Yangtze boatmen to align their bodies through sound in rapids, fog, and broken visibility. Although the chants disappeared after the Three Gorges impoundment, their underlying algorithm of synchronization remains embedded in the structure of the sound. Through the four-part rhythm of calm-water, pre-rapid tension, rapid-force alignment, and post-rapid release, this piece renders visible an ancient form of collective intelligence within a contemporary frame.

《云梦古舞》从云梦泽的湿地节奏出发,

追索楚舞的动作语法:

长袖的展开、细腰的三道弯、贴地的绕步与激楚的节奏。

本文将身体视为感知环境的工具,

并以武汉三座高铁枢点——武汉站、汉口站、武昌站——

对应“向前、向地、向回”三种节奏结构,

让楚舞的动势在当代城市中重新显形。

这不是对古舞的复原,

而是一种动作在时间里持续重复后的文明回声。

Cloud-Dream Ancient Dance begins with the rhythms of Yunmeng Marsh

and traces the movement grammar of Chu dance—

the expanding sleeves, the three-curved waist,

the ground-bound circling steps,

and the sudden surge of Ji Chu rhythm.

The body is treated as a sensor of environment,

while Wuhan’s three major railway hubs—Wuhan, Hankou, and Wuchang Stations—

mirror three movement logics:

forward, downward, and turning back.

Through these spatial rhythms,

the dynamics of Chu dance become visible again in the modern city.

This is not a reconstruction of the past,

but an echo carried by actions

that continue to be done—and redone—across time.

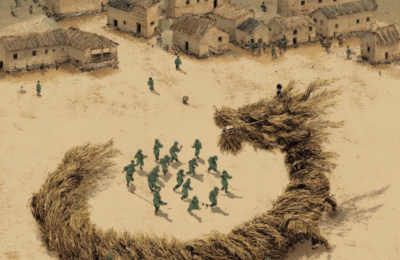

这篇《草把龙》写的是潜江湖区的一种路上舞蹈。

它的龙身由稻草扎成,靠步法、队形与愿望被撑起来。

文章整理它的来源、动作结构、礼制用途、地理现场

以及高铁到来后,让外来者能真正抵达的那条“年节之路”。

草把龙的核心不是保存,而是每年再走一次。

This “Grass Dragon” piece looks at a road-based ritual dance from Qianjiang’s lake region.

Its straw body is held together by steps, formations, and collective intent.

The article traces its origins, movement grammar, ceremonial functions,

the wetland geography that shapes it,

and how high-speed rail opens access to its annual route.

Its essence is not preservation, but repeating the path each year.

端公舞,流传于湖北襄阳南漳的山村,是一种以“迎、敬、安、送”四段为核心的仪式性舞蹈。

它不是舞台艺术,而是村落用来祈安、驱疫、送别、镇宅的实际做法。

六步、舞式、指诀、队形——

动作在身体里保存着楚地巫仪的逻辑;

村落的需要,让这套方法持续运作两千年。

郑渝高铁让南漳成为“可抵达的传统”。

空间被打开,节律被看见;

舞没有改变,只是多了一条能够抵达它的路径。

端公舞提示我们:

文明不只靠记住,也靠继续做。

那些在时间里不断被重复的动作,

正是文明真实的心跳。

The Duan Gong Dance, preserved in the mountain villages of Nanzhang in Xiangyang, Hubei, is a ritual dance built around four movements—welcoming, honoring, settling, and sending.

It is not a stage performance, but a living practice used to bless, appease, protect, and restore order within the community.

Six basic steps, ritual poses, hand seals, and shifting formations

carry the logic of ancient Chu shamanic traditions—

sustained not through written records,

but through the needs and repetitions of daily life.

The Zhengzhou–Chongqing High-Speed Railway has made Nanzhang newly reachable.

Space opens; rhythm becomes visible.

The dance remains unchanged—only the path to reach it has expanded.

The Duan Gong Dance reminds us that

civilization endures not by remembering alone,

but by continually being done.

The gestures repeated across time

are the true heartbeat of a culture.