一縷微腥的香,穿越水雲與書案之間。

不是每種香氣都天生馥郁,有些必須經歷煎熬與淬火,才顯清芬。

本篇探尋的是「黃庭堅與螺甲香」交織的幽微篇章。黃庭堅是宋代文壇巨擘,江西詩派之祖,更被後世尊為「香聖」。

在千帆過盡的詩卷之外,他以一縷縷焚香的煙霞,洗練心魂、鍛煉性情。螺甲香,是靈魂的修練。香煙繚繞間,他以筆作舟,渡過現實的滄浪,也讓一抹海的氣息,融入了詩心與夢境。

香徑其地|贛江畔的詩魂

贛南,既是黃庭堅的流放之地,也是他精神蛻變的香學之徑。

在贛江畔,他焚香靜坐,遠離朝堂喧囂,與空性為伍。螺甲香的特性——陰中有陽、腐中出香,彷彿也是一帖他寫給自己心靈的安慰劑。

古人言:「香可清心,亦可照影。」

螺甲香需在烈火中浴火重生,而黃庭堅亦在貶途中寫下無數不朽詩篇。他說:「清風徐來,水波不興」,但那一縷香氣卻已穿過千年書卷,仍在贛江一隅悄悄浮動。

香學其義|螺甲不香,故能成香

現代合香講究君臣佐使,古人則更講究香料的性格與轉化。

螺甲香不是天生馥郁之物,反而帶有一種孤傲與抵抗。

它像黃庭堅一樣,不肯隨俗、不輕與合,卻在長久的隱忍與修煉中,自成風骨。

香不是用來討喜的,是用來見證的——見證時間如何從雜質中煉出本真。

沿香而行|香徑與文脈的連結

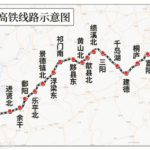

若你自南昌出發,乘坐贛深高鐵,抵達贛州,步入黃庭堅流放之地——

這不只是文學朝聖,更是一場嗅覺與詩心的覺醒之旅。

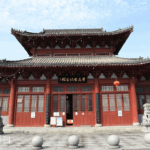

你可以走訪黃庭堅紀念館、步入賜閣巷,在舊屋中嗅聞微弱香氣的迴音。那不是蠟燭香,也不是花露香,而是來自一千年前詩人案上燃起的「螺甲沉香」。

結語|香若其人,人如其香

黃庭堅說:

「欲雨鳴鳩日永,下帷睡鴨春閒。」

他看似戲言,卻道出焚香清供、與天地並坐的閒情逸致。

螺甲香不是濃烈之香,它的存在如同詩人遺世的文字,淡而不薄、隱而不滅。

千年之後,我們在鐵道與文字之間,仍可尋見那縷「百煉」之香。它從江南出發,繞過風塵與權謀,最終留在一頁詩後、一封煙雨南行的舊信裡。

黃庭堅:《有惠江南帳中香者戲贈二首》

他自號「山谷道人」,一生宦游顛沛,屢遭貶謫,但也因此與香結緣,沉靜於焚香書畫之境。

在《有惠江南帳中香者戲贈二首》中,他寫道:

「百煉香螺沉水,寶熏近出江南。

一穗黃雲繞几,深禪想對同參。」

「螺甲割匀焚耳,香材周磨拂塵。

欲雨鳴鳩日永,下帷坐對香爐。」

譯文:

歷經百煉的香螺沉入水中,名貴的香料出自江南。。

一縷金黃煙霧繞著案几,靜坐參禪之時與友人共悟。

將螺甲整齊切割焚燒,香料圓潤細磨以去塵垢。

天將下雨,鳴鳩長鳴,我垂簾靜坐,對著香爐冥想。

他所說的「螺甲香」,正是從南海貝螺提煉而成的香料,原本氣味腥臭,需經炮炙焚煉、搭配諸香調和,方能顯出幽微清芬——這種由腐轉芳的質變,恰恰呼應了黃庭堅的人生哲學:熬過萬難,才能返璞歸真。

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Mehr Informationen從杭州到南昌,一段串聯名城名山的黃金旅程

杭昌高速鐵路是一條連接浙江杭州、安徽黃山與江西南昌的高速鐵路,全長約560公里,設有18座車站,最高營運時速達350公里,是中國「八縱八橫」高速鐵路網的重要支線之一。

旅客可從杭州南站出發,經千島湖、黃山、景德鎮、鄱陽湖,最終抵達南昌東站,全程風光絕美。這條黃金旅遊線路沿線串聯西湖、富春江、黃山、鄱陽湖、滕王閣等國內知名5A級景區,是遊覽江南與贛鄱的首選。

沿線車站融合了徽派建築、人文設計與現代功能,尤其杭黃段,更像是行駛在畫卷中的旅程。杭昌高鐵不僅大幅縮短了杭州至南昌的交通時間,也開啟了浙江西部富陽、桐廬等地的高鐵時代。

目前,江西段已啟用「鐵路e卡通」、約號進站等智慧交通服務,還推出了30日定期票與20次計次票,為常旅客提供更多彈性選擇。

無論是賞湖遊山、探索人文古鎮,或是體驗現代高鐵之便,杭昌高鐵都將為您開啟一段悠然的文化之旅。

資料來源:杭昌高速铁路

和諧號 CRH380A 型電力動車組

和諧號 CRH380A 型電力動車組(又稱 CRH2-380 型),是中國專為時速 350 公里等級高速鐵路設計的第二代高速列車,由中車青島四方機車公司在原 CRH2C 型基礎上研發而成,採用鋁合金空心型材車體,結構輕巧、安全穩定。

此車型經本土化改進,成為中國首批實現時速 350 公里商業營運的高鐵列車之一。自 2009 年起,時任鐵道部向南車青島四方採購共 140 列此型號列車(含長短編組),總值約 450 億人民幣。

CRH380A 採用動力分散設計,列車牽引能力更強、提速更快,最高測試時速超過 400 公里,滿足京滬高鐵等高標準路線的需求。車體外型經空氣動力學優化,行駛時更為平穩安靜,是現代中國高鐵速度與科技的代表作之一。

資料來源:和谐号CRH380A型电力动车组

📜 本作品已提交版权保护程序,原创声明与权利主张已公开。完整说明见:

👉 原创声明 & 节奏文明版权说明 | Originality & Rhythm Civilization Copyright Statement – NING HUANG

节奏文明存证记录

本篇博客文为原创作品,由黄甯与 AI 协作生成,于博客网页首发后上传至 ArDrive 区块链分布式存储平台进行版权存证:

- 博客首发时间:请见本篇网页最上方时间标注

- 存证链接:aabaad0e-eaf8-4077-83b6-b0381c0711c1

- 存证平台:ArDrive(arweave.net)(已于 2025年7月5日 上传)

- 原创声明编号:

Rhythm_Archive_05Juli2025/Rhythm_Civilization_View_Master_Archive

© 黄甯 Ning Huang, 2025. All Rights Reserved.

本作品受版权法保护,未经作者书面许可,禁止复制、改编、转载或商用,侵权必究。

📍若未来作品用于出版、课程、NFT或国际展览等用途,本声明与区块链记录将作为原创凭证,拥有法律效力。

《万舞|用身体向天祭神》

《万舞|用身体向天祭神》是一篇从“身体”重新理解上古礼乐体系的文章。

文舞与武舞两条身体路径,共同构成万舞的双轨结构:

羽的亮度来自劳动的身体,干戚的重量来自献的姿态。

本文从甲骨卜辞、礼乐传统与身体工法分析出发,

重建万舞的动作逻辑——身体如何从生活而来,再被举向神。

它不是求雨的身体,而是祭天的身体;

不是呼喊,而是呈献。

万舞的底层算法,只有一个字:祭。

“Wan Dance|A Body Offered to the Sky” reinterprets one of the earliest ritual dances in ancient China through the lens of bodily practice.

Wan Dance contains two intertwined bodies—

the wen body of feathers, bright and open, and the wu body of shield and axe, heavy and offering-oriented.

Drawing from oracle bone inscriptions, Zhou ritual aesthetics, and agricultural movement patterns,

this article reconstructs the embodied logic of Wan Dance:

how actions grow from labor, and how the body is lifted toward the divine.

It is not a body that asks, but a body that offers.

The fundamental algorithm of Wan Dance is a single word: sacrifice.

《雩舞|用身体向天求雨》

《雩舞|用身体向天求雨》探讨中国最早的求雨仪式——雩。以甲骨文、先秦典籍与礼制考证为基础,呈现雩舞的起源、羽饰技术、八重声音结构、巫与童子的角色、旱雩与常雩的制度分化,以及祈雨时身体如何成为人与天之间的最后语言。文章以“身体力”为线索,强调雩舞是古人面对极端旱灾时,以动作、呼号、歌哭共同组成的“求的身体”。

“Yu Dance|When the Body Begs the Sky for Rain” examines one of China’s earliest rain-invoking rituals—Yu (雩). Drawing on oracle bones, pre-Qin texts, and ritual scholarship, the essay presents the origins of Yu-dance, the function of feathers, the structure of its eight sonic components, the roles of shamans and children, and the distinction between drought rituals (han-yu) and seasonal rituals (chang-yu). Through a “body-force” perspective, the piece highlights how, in moments of extreme drought, movement becomes the final language between humans and the sky.

《Pole Dance 钢管舞|垂直的身体》

这篇文章以“垂直的身体”为线索,重新书写钢管舞的历史、身体结构与文化误读。钢管舞并非性感的代名词,而是一种对抗地心引力的身体技术:靠力量、皮肤、摩擦力、疼痛与上升组成的训练体系。从杂技到工地,从夜店到竞技场,它的身体方向始终只有一个——向上。文章将起源、身体算法、社会争议与上升意义整合成一条“离开地面”的文明叙述,展示身体如何在半空中重新找到自己的方向。

This essay explores pole dance through the lens of a “vertical body” — a body that chooses ascent over movement on the ground. Far from being a symbol of eroticism, pole dance is a discipline built on strength, friction, skin, pain, and elevation. Its history stretches from acrobatic pole climbing to construction sites, from nightclubs to professional sport, yet its direction has remained constant: upward. Integrating origin, bodily mechanics, cultural misunderstandings, and the meaning of ascent, the essay repositions pole dance as a practice in which the body rewrites itself the moment it leaves the ground.

《Belly Dance|肚皮会说话的身体》

这篇文章从肚皮舞的源起、身体算法、到不同国家的风格差异,回到现代课堂里的自我亮度。

肚皮舞曾经是神庙里的祈愿,后来成为城市中的表演,如今是一种身体的语言学——用腹部、骨盆、波浪与震动,重新练出属于自己的方向感。

文章最后回到 2026 年 2 月 28 日斯图加特的现场:当教练带着全班复述 “I am beautiful!” 的那一刻,肚皮舞不再是求神,而是点亮自己。

“Belly Dance|The Body That Speaks Through the Belly”

This essay traces belly dance from its ancient ritual origins to its contemporary forms: the core-centered philosophy, the algorithm of isolation and recombination, and the stylistic differences among Egyptian, Turkish, and Lebanese traditions.

Modern belly dance becomes a language of the body—using waves, figure-eights, pelvic rhythms, and vibration to reclaim direction from within.

The article returns to Stuttgart on February 28, 2026, when the instructor guided the class to repeat “I am beautiful!”—a moment when belly dance ceased being a prayer to the divine and became an act of self-illumination.

《Maculelê|棍棒击出来的身体》

Maculelê 起源于巴西巴伊亚的非裔社区,是一种以棍击为核心的勇士舞蹈。

在现代课堂里,这套来自甘蔗园的节奏语言被重新点亮:

棍子替代刀锋,四拍建立身体的节奏线;

排列与圆阵成为对齐的空间;

每一拍都在训练身体如何在节奏中保持稳定。

这篇文章从器物、空间到节奏,追索 Maculelê 的身体算法,记录一次在 2026 年 2 月 8 日课堂里,

身体如何在第四拍被重新排列。

Maculelê, rooted in Afro-Brazilian communities of Bahia, is a warrior dance built on the rhythm of sticks.

In the contemporary studio, this ancestral language is reactivated:

sticks replace blades, the four-count structure resets the body,

and formations—circles or lines—become spaces for alignment.

Each count refines how the body stays steady inside moving rhythm.

This article traces the bodily algorithms of Maculelê through its tools, space, and rhythmic logic,

documenting how, in a class on February 8, 2026,

the body was reorganized by the force of the fourth beat.

《Zumba|现代人的集体身体》

Zumba 由一位哥伦比亚教练意外开启,却以南美节奏为骨,将 Merengue、Salsa、Cumbia、Reggaeton 重新组合成一种“当代的身体”。本篇从起源、身体算法、集体算法,一路写到尾之声,探讨 Zumba 如何让现代人在被压得满溢的生活里,用摇动重新听见自己。它不仅是健身课,而是一种没有祖先、没有禁忌、没有门槛的当代集体——让身体因节奏而成立,让情绪因呼吸而松开,让现代人得以以最温柔的方式回到自己。

Zumba began as an accident by a Colombian instructor, yet it draws on the full spectrum of South American rhythms—Merengue, Salsa, Cumbia, Reggaeton—to form what this essay calls “the body of the contemporary world.” Through origin, body algorithms, collective algorithms, and final resonance, this piece explores how Zumba allows modern individuals to hear themselves again through movement. Beyond fitness, Zumba becomes a ritual-free, borderless collective space where the body reclaims breath, emotion reorganizes itself, and a quiet form of self-return becomes possible in an overwhelming world.