这篇文章的灵感来自纪录片《寻色中国》第一集「黄色」篇章。

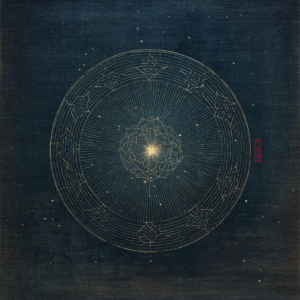

以苏州织造流转千年梦境,织出光与土之间的永恒诗篇,致敬中华文明中最温暖的色彩。

苏州丝织的柔韧与光泽,在高铁飞驰之间,再次发出低语。

黄色,是土地的根,是文明的肤,是日光掠过织机时的一声轻响。

在京沪高铁飞驰的速度中,苏州站宛如一枚静谧的绣针,将古老的织造记忆,缝入现代的脉络之中。

从一缕光,到一匹绢,千年的时光在指尖缓缓流转。

《流光织造》由此而生。

如果世界有最暖、最温柔的颜色,那一定是黄。

黄,是光之首,是土之色,是天地初分时,光亮在大地上洒下的第一道光点。

在《说文解字》中,“黄”,是江水光照大地而成的颜色,为光照之色,是埋藏着光明与生命力量的温暖之色。

在中国文化里,黄,是五方正色之一,代表中央,象征大地,连接东西南北的心脉。

黄土,养育了千营万落;

黄河,流过中原,留下了历史的痕迹。

起初,黄色在上古文明中,就是合天地之归心;随着秋季的到来,黄色也成为中华文明中最契合中心转换的色彩。

在江南水乡,有一缕光,是丝线织出的时间。

苏州织造,起于明代,盛于清世,作为皇家直属的织造局,肩负着为皇宫织就龙袍、朝服与贡品丝缎的重任。绫罗绸缎间,藏着的是江南最细腻的匠心,最华贵的审美。妆花如云,缂丝如画,宋锦如诗,每一寸织物,都是时间与技艺交缠的回响。

这里不仅是丝绸之都,更是礼制与审美的合一之地。龙纹缂丝,织的不只是锦缎,更是天子的威仪,盛世的温柔。

苏州织造,是织在衣上的江南,是盛世之下的一抹风雅。它将一城烟雨、一段丝路、一缕工艺,织成中国最柔韧也最耀眼的文化标识。

它不仅为皇宫而织,也为千年江南留下了一张永不褪色的名片。

图片来源:故宫博物院

在《红楼梦》里,黄色,是藏在最温柔、最远征相思中的一抹光。

薛宝钗一身蜜合与葱黄色,藏着清淡精致与内敛的气息。

在红楼梦里第八回,宝玉看宝钗:

蜜合色棉袄,玫瑰紫二色金银鼠比肩褂,葱黄绫棉裙,一色半新不旧,看去不觉奢华。……………(宝钗)一面解了排扣,从里面大红袄上将那珠宝晶莹黄金灿烂的璎珞掏将出来。

蜜合色,介于蜂蜜与琥珀之间,色泽温暖而柔和,带有淡淡的中性色调。

在《红楼梦》中,曹雪芹以色写人,尤为细腻。薛宝钗常着黄色系衣物,如蜜合色、葱黄等,反应她性格中的稳重、温婉、内敛与持重。黄色于她,不张扬,却自有分寸之美,宛如一抹柔光,静静照亮她的人格边界。

在中国传统节气中,黄色常被视为季节转换的代表色,尤其与春季和秋季密切相关。春日的嫩芽、秋日的稻穗,都呈现出黄的不同层次。

秋分时节,稻谷成熟、田野金黄,是中国农民庆祝丰收的重要时刻,也被定为“中国农民丰收节”。在春秋交替之间,黄色不仅反映了自然界生长与成熟的节奏,也承载了人们对土地温润、万物有序的理解与尊重。

今日,花一程时光,踏上京广高铁,一路南下,抵达苏州站。

这座车站,仿佛一缕细黄的丝线,纯纯地绘着一段最温暖的时光。

黄,不只是大地的颜色,也不仅是光的色调。

它是在光与土之间,给予世界的一场温柔期盼,

如同回忆,如同希望,

也如同,一场长长的、缓缓流淌的光。

苏轼 《轼以去岁春夏,侍立迩英,而秋冬之交,子由》

曈曈日脚晓犹清,细细槐花暖欲零。

坐阅诸公半廊庙,时看黄色起天庭。

译文:

晨曦中阳光微弱,天空尚且清冷,细小的槐花在温暖中缓缓飘落。

坐在廊庙之间,静看群臣聚集,偶尔抬头,便见一片祥瑞的黄色在天庭升起。

这首诗描绘了清晨朝堂的肃静与庄严,借黄色祥云寄托对政通人和的期望。黄色在天庭升起,不只是色彩的描写,更象征着盛世的期许。

资料来源:轼以去岁春夏,侍立迩英,而秋冬之交,子由

歌曲 《流光织梦》|黄色 · 苏州织造

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

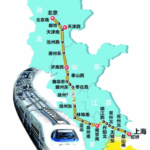

Mehr Informationen京沪高铁

京沪铁路与京沪高铁简介|南北大动脉的穿越之旅

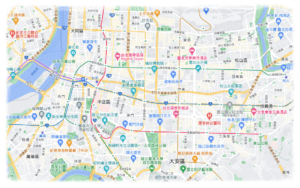

京沪铁路是中国连接北京市与上海市的重要铁路干线。北起北京站,南至上海站,正线全长1318公里,是一条承载客货运输的重要南北通道。

沿线地区经济发达,文化底蕴深厚,自然与人文景观交相辉映。京沪铁路不仅支撑了南北物资运输,也是旅游和城市间交流的重要纽带。从黄河、淮河到长江,这条线路穿越了华北、华东最富饶的土地,是中国最繁忙的传统铁路干线之一。

随着运输需求的不断增长,京沪铁路面临运输能力饱和的问题。为了缓解压力并提升速度,中国启动了京沪高速铁路项目。

京沪高铁于2008年开工建设,2011年6月30日全线通车。线路全长1318公里,设有24座车站,起点为北京南站,终点为上海虹桥站。列车设计时速达到380公里,是世界上一次建成线路最长、标准最高的高速铁路之一。高铁沿途跨越海河、黄河、淮河、长江四大水系,大部分路段以桥梁形式铺设。

京沪高铁不仅是交通工程的奇迹,也是中国高速铁路技术和标准体系的重要代表。它缩短了南北城市之间的时空距离,约四小时即可从北京抵达上海,大大促进了区域经济一体化和沿线城市的发展。

京沪铁路和京沪高铁,共同构成了中国“八纵八横”国家铁路网的重要支柱,也是游客和旅人们感受南北风貌、领略千里风光的最佳通道。

图片与资料来源:京沪高速铁路

京沪高铁有多快?时速350km/h 北京到上海只要4小时!《中国高铁》第1集

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

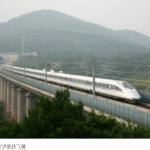

Mehr Informationen京沪高铁创造奇迹:时速486.1公里,书写中国速度传奇

2010年12月3日,在京沪高铁枣庄至蚌埠段的联调联试中,中国南车集团研制的“和谐号”CRH380A新一代高速动车组,创造了时速486.1公里的世界铁路运营最高速度纪录。这一成绩,相当于喷气式飞机低速巡航的速度,标志着中国高铁技术迈入全球领先行列。

此次创纪录的列车,是世界上运营速度最快、科技含量最高的动车组。它的最高运营时速为380公里,常规运营时速为350公里,在气密性、智能化控制、环保设计等方面全面创新。

CRH380A的外形设计亦堪称经典。其流线型车头灵感取材于“长征火箭”,在经过17项75次仿真分析、完成22项试验验证后定型,不仅气动性能卓越,还寓意着中国高铁向航空科技领域比肩腾飞。

图片与资料来源:“和谐号”动车组再次刷新世界铁路最高运营时速

📜 本作品已提交版权保护程序,原创声明与权利主张已公开。完整说明见:

👉 原创声明 & 节奏文明版权说明 | Originality & Rhythm Civilization Copyright Statement – NING HUANG

节奏文明存证记录

本篇博客文为原创作品,由黄甯与 AI 协作生成,于博客网页首发后上传至 ArDrive 区块链分布式存储平台进行版权存证:

- 博客首发时间:请见本篇网页最上方时间标注

- 存证链接:af7645b4-9149-4dfc-ac12-df3edcc863ac

- 存证平台:ArDrive(arweave.net)(已于 2025年7月7日 上传)

- 原创声明编号:

Rhythm_Archive_05Juli2025/Rhythm_Civilization_View_Master_Archive

© 黄甯 Ning Huang, 2025. All Rights Reserved.

本作品受版权法保护,未经作者书面许可,禁止复制、改编、转载或商用,侵权必究。

📍若未来作品用于出版、课程、NFT或国际展览等用途,本声明与区块链记录将作为原创凭证,拥有法律效力。

《楚地龙灯|光如何在乡土上行走》

《楚地龙灯》不是在描述一个春节的热闹项目,而是在追踪一种“湿地身体算法”如何被点亮、放大,并以光的方式重新走过乡土。龙灯的动作——方向先行、摆幅恒定、中心推进——并非表演技巧,而是湿地文明古老的走路方式,被几十个身体合成一条脊柱,在黑夜中显形。火不是舞台效果,是显影剂;光不是照明,是路径。龙灯的意义,不在装饰,不在节庆,而在于:一个社区如何通过身体对齐、火光校准与路径确认,完成一年一次的“文明重新上路”。

“Dragon Lanterns of Chu” is not a study of festive spectacle but an inquiry into how a wetland civilization reactivates its oldest movement algorithms through light. The dragon lantern’s motions—direction-leading, amplitude-holding, core-driven—are not performance techniques but embodied memories of how people once moved across unstable ground. Dozens of bodies merge into a single spine; fire becomes a revealing agent; light becomes a pathway. The significance of the dragon lantern lies not in decoration or celebration but in how a community recalibrates itself—by aligning bodies, syncing rhythms, and retracing the essential routes that allow its world to start again each year.

《楚式营建学·全系列导航》|文明操作系统的结构说明

《楚式营建学》是一套从湿地、时间、材料到系统算法的文明操作系统。

本导航汇整九篇正传与两篇外传,展示楚人如何让城市与文明“被生成”——

空间由湿地读出,结构由节律推动,秩序由系统达成。

Yingjian(营建)不是工程,而是让世界继续成形的文明能力。

Chu Yingjian Studies presents a civilizational operating system derived from wetland dynamics, temporal rhythms, material logic, and systemic coordination.

This master navigation outlines the nine core chapters and two extended dialogues, showing how Chu cities and their world were not built but generated.

Yingjian is not engineering—it is the civilizational capacity that allows forms, systems, and worlds to continue emerging.

《以身为舟|采莲船和划龙船:楚地湿地文明的年节步法》

本篇从采莲船、彩船与旱地划龙船等年节船舞切入,

不以器物形制为主,而以“身体作为船”的底层算法为核心。

通过三个动作结构——方向先行、摆幅恒定与中心推进——

解析湿地文明如何在河网退去之后,

仍以步法保存“水的逻辑”。

文章提出:

不同地区的年节船舞并非彼此模仿,

而是同源于一条共同的湿地身体记忆。

在年节中,人以身为舟,

让一条看不见的河再次被走出来。

This essay examines New Year “boat dances” across the wetland cultural belt—

from lotus boats to decorated stage-boats and land-based dragon boats—

focusing not on their shapes but on the shared bodily algorithm that animates them.

Through three structural principles—direction leading before steps,

constant lateral sway, and core-driven propulsion—

the text reveals how wetland civilizations preserve the logic of water

through movement long after the waterways have shifted or vanished.

Rather than regional imitation, these boat dances emerge from a common

embodied memory shaped by river networks.

In the New Year season, the body becomes a boat,

and an unseen river rises again under the dancers’ feet.

《楚式营建学 · 外传二|楚辞 × 考工记的地下恋爱》

《楚式营建学 · 外传二》是一场关于“结构与诗性如何在地下相遇”的实验性写作。

《考工记》代表北方的秩序与尺度,《楚辞》代表南方的气息与生成。

两者原本不相交,却因同被封入墓室而在黑暗中开始对读。

本文以拟人化方式,重建两千三百年前两种世界观的交汇:

他们彼此质疑、彼此偷学,最终生出一个孩子——

楚式营建学:一种由地景、时间、材料、身体、制度共同驱动的文明建构心智。

这是楚文明底层逻辑的再现,不是爱情故事。

那是两部古书在黑暗中点亮彼此的时刻。

“Chu Yingjian · Extra II” is an experimental narrative about how structure and breath meet underground.

The Kaogongji stands for northern order—measure, alignment, systemic clarity.

The Chuci carries southern sensibility—water, wind, emergence, and the pulse of living forms.

Placed together in a tomb 2,300 years ago, the two texts begin to read each other in the dark.

This chapter personifies their dialogue and traces how two worldviews slowly interweave—

questioning, borrowing, transforming—until they generate a single child:

Chu Yingjian:a civilizational building-mind shaped by landscape, time, materials, the body, and systemic order.

It is not a love story.

It is the moment two ancient grammars discover they share the same world.

《楚式营建学 · 外传一|文明回声:楚式营建与高铁思维的结构对应》

《文明回声》不是在寻找“影响链”,

而是在描述一种更深的结构事实——

当文明必须处理高度复杂的系统时,

会独立长出相似的组织方式。

楚式营建并未影响现代高铁,

高铁也没有继承古代楚城的任何技术或形式。

但两者都在面对各自时代的巨大复杂性:

湿地、湖泽、礼制、材料、节律、战争、迁徙;

速度、网络、调度、节点、精度、迭代、共生。

它们之间的相似,

不是传承,

不是源流,

而是 结构的趋同。

古代楚文明留下的礼器系统、编钟系统、城址系统、

与现代高铁的规模、系统、技术、迭代、精度、共生六大思维,

在结构上相互映照——

显示出文明在面对复杂世界时

都会发展出一套“让系统能够成立”的心智。

本篇是一次跨越两千年的

结构层级的对照实验:

不求证明,不作推演,

只展示文明在深处

如何自然地长成类似的形状。

Civilizational Echoes is not a search for historical influence.

It is an attempt to describe a deeper structural fact:

when a society must organize a highly complex system,

it tends to grow similar forms of thinking—independently.

Chu engineering did not shape China’s modern high-speed rail,

nor did high-speed rail inherit anything from ancient Chu cities.

Yet both faced the full weight of complexity in their own eras:

wetlands, water systems, ritual structures, materials, rhythms, migration;

speed, networks, dispatching, nodes, precision, iteration, coexistence.

Their resemblance is not lineage,

not transmission,

but structural convergence.

The ritual vessels, bell systems, and cityscapes of ancient Chu

mirror—in structure rather than origin—

the six paradigms of the modern high-speed rail system:

scale, systems, technology, iteration, precision, coexistence.

This chapter is a cross-epoch structural experiment,

showing how civilizations,

when confronted with complexity,

naturally grow toward similar organizational logics—

without contact, without inheritance,

purely through the demands of the world they must sustain.

《楚式营建学之九|营建世界的方式:楚文明的生态系统设计》

本篇作为《楚式营建学》的世界观封顶章,从“城市如何长成”提升到“世界为何能被生成”的层级。楚人以时间为节律、以湿地为形势、以材料为结构语言、以身体为路径生成、以制度为安定核心,使营建成为一套协同系统。本文进一步提出楚文明的三层同构模型:宇宙的反辅、社会的差异互成、城市的自然生长,并指出楚文明的核心不是建造物,而是一种让世界得以持续生成与维持的操作方式。

As the conceptual capstone of Chu Yingjian Studies, this chapter elevates the discussion from “how cities grow” to “why a world can emerge at all.” The Chu viewed time as rhythm, wetlands as spatial logic, materials as structural language, the human body as path-maker, and institutions as stabilizing centers—forming a coherent generative system. This essay presents the Chu model of reciprocal formation across three scales—cosmos, society, and city—and argues that Chu civilization is fundamentally a life-system operating system, rather than an architectural tradition.