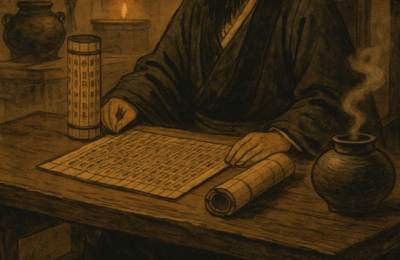

《算力之源:从楚简〈九九术〉到清华Excel〈算表〉的先秦数学革命》

先秦文明并不只在思想的辩论中闪光,它同样在数字的缜密中崛起。从秦家咀楚简《九九术》到清华简《算表》,再到九店楚简中神秘的数量记录,我们得以窥见一个“计算力”成为国家治理底层动力的时代。口诀是操作系统,算表是旗舰应用,而田亩、军粮与酿造的日常数据,则构成了这个数学生态真正的运行场景。这场沉默却深刻的“先秦数学革命”,不仅让楚国的官吏能够驾驭土地、仓储与资源,也重新定义了权力、知识与国家机器的节奏基础。 Pre-imperial China did not rise on ideas alone—it rose on numbers. From the Chu bamboo-slip Nines Multiplication Table (Jiujiu Shu) of Qin-jiazui, to the sophisticated Calculation Table (Suan Biao) of the Tsinghua manuscripts, and the enigmatic quantitative records from Jiudian, a hidden “computational ecosystem” emerges. Memorized formulas functioned as the operating system; the calculation table acted as a high-performance application; and the daily data of land, grain, and brewing formed its real-world execution logs. This quiet yet transformative “mathematical revolution” empowered officials to manage resources with unprecedented precision—and reveals a new rhythm of how early states understood power, knowledge, and governance.